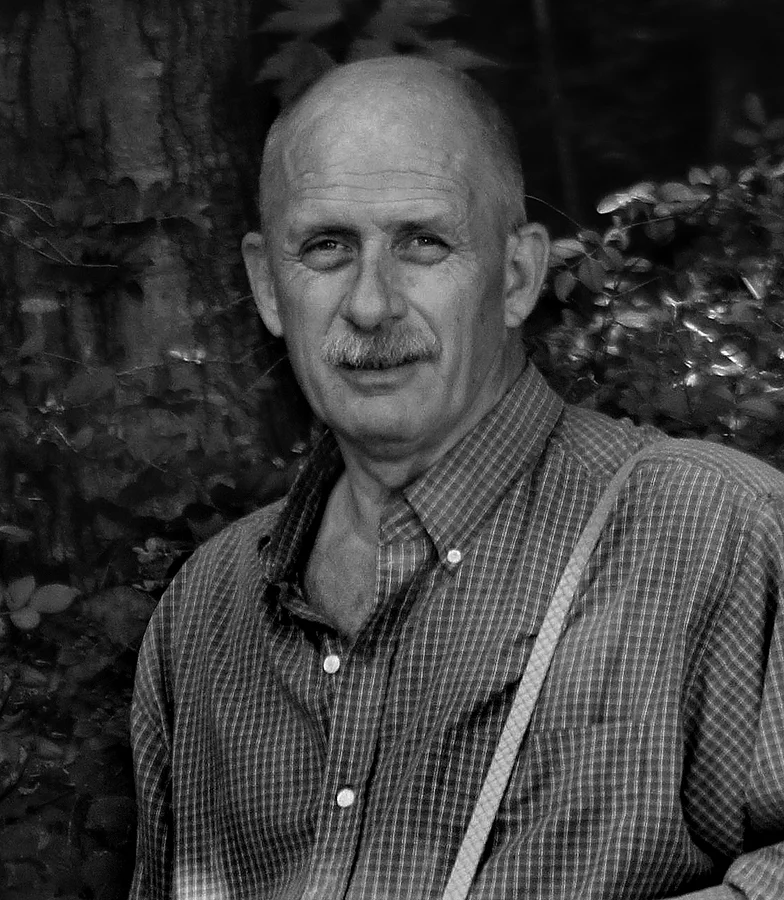

Audey Ratliff:

Shaping a Life

by Hermon Joyner

With many of the mandolin builders I talk with, there is the idea that once a builder gets past their 50th mandolin, their skills are fairly well matured and they have learned all that they need to be a first-class professional builder. And given that most solo builders produce between 10 and 20 instruments a year, getting to 50 can take several years and it’s not unusual for their total output to number anywhere from 50 to a couple of hundred at the most. But then you meet someone like Audey Ratliff.

At the time of this article being written, the 57 year old Ratliff was just putting the strings on mandolin No. 1107 in his workshop in Church Hill, Tennessee. With his typical dry sense of humor, Ratliff said, “Well, that’s a lot of mandolins. Yeah.”

Ratliff is quick to give credit where credit is due and he points out that he had some help along the way to get to that high number. He said, “I had employees for a while, I don’t know, seven or eight years, maybe; and that’s where that high number comes from. Somewhere around 600 or 700 were made when I had employees. Which leaves me with about 400 on my own, but that’s clicking along pretty good for one guy.”

And that is a bit of an understatement.

Audey Ratliff grew up with bluegrass music in his blood. His dad was a Dobro player who played all up and down the eastern seaboard and Audey himself took to the mandolin, though he is also proficient on the guitar, bass (he recently played bass in Ralph Stanley’s band for eight months on tour), and the fiddle. Ratliff is probably one of the most accomplished mandolin players who is also a mandolin builder. His solo CD, Piece of Cake, is a flat-out excellent recording with inventive and tasteful mandolin solos and features his own singing, which reminds me of Tony Rice’s voice in his prime. He’s also taught mandolin for many years. Ratliff, in fact, has the distinction of being Adam Steffey’s first mandolin teacher. He still teaches mandolin and currently has about 12 students. But it was the fact that he is left-handed that pushed him into building mandolins.

photo by Charles Johnson, mandolin world headquarters

Finding left-handed F-style mandolins is hard to do. Ratliff’s first professional leftie mandolin was built for him by Wayne Henderson in 1977 when Ratliff was 20 years old. It was also about the time that Roger Siminoff’s book on building bluegrass mandolins came out. Ratliff said, “That’s how I started into it. Being left-handed, I had to have a left-handed mandolin built for me, because I didn’t know any better at the time. Then the Roger Siminoff book came out, which I ordered, read about four or five times, and decided that I believe I can do that. And it’s been downhill ever since.”

He built his first mandolin in the spring of 1981 and then quickly made another two. All three sold as fast as they were available. His third one was bought by Adam Steffey (in fact, Steffey has owned and played three Ratliff mandolins over the years, Nos. 3, 17, and 82). Ratliff decided to devote all his time to building and became a full-time mandolin builder in 1982 and that’s what he’s been doing ever since.

Ratliff wasted no time and the Siminoff book was a big part of that, at least at first. Ratliff explained, “The Roger Siminoff book is a great start and it lays it all out. You have to bend the sides and you have to carve the top and back and you have to hang the neck on it. The first ones I built used the exact same techniques that he used in the book, but now I probably don’t used a single thing in that book. Nothing I do now is done in the same manner because over the years I’ve evolved away from that book. I still follow the steps, but it’s just that the tools I use in the process to make that piece is completely changed. It doesn’t even resemble that book at all now. That basic thing is that you have to build a box and hang a neck on it. But I assure you, if it wasn’t for that book, I’d certainly have a different job today.”

Probably the biggest deviation from the norms of mandolin construction is how he “carves” the tops and backs of his instruments. He doesn’t use chisels, except for the scroll details, or finger planes, or dupli-carvers, or CNC machines. Instead, he has found his own unorthodox way of shaping those plates. Ratliff explains, “I use a big auto body side grinder/sander to do the bulk of the top carving to get it really roughed down. It’s so much faster. You can lay it down in there and you’ve got a big seven-inch disc on it and once you learn how to use it, you can get relatively close to the final shape and can then go in there with a pad sander and smooth everything out. I usually carve the insides first and get the bowl shape I want and then I’ll take everything else outside down to a certain thickness from that finished inside shape. And then about the only time I lay a chisel to it is just around the scroll. I can pretty much make an A-style body, which doesn’t have a scroll, without ever touching the body with a chisel.”

And by now, Ratliff doesn’t even use templates. Each piece of wood is evaluated and its thickness is determined by his experience and intuition. He said, “Well, my template is just a depth gauge. The actual center of the top, the deepest point, I just use that depth gauge and after that I just kind of put my hand to it and make sure it’s got the contour that I like. I’ve made actual templates to do the same thing, but then you get a softer piece of wood or one that feels a little stiffer and you know to do it a little bit different. After a while, I just look at the wood and I go by the depth of the deepest point and then I just kind of wing it. They all come out pretty close to the same, anyway.”

photo by charles Johnson, mandolin world headquarters

Carving the top and back plates is a big part of creating the sound of the mandolin, and what Ratliff is aiming for is a bluegrass mandolin. And this is a never-ending learning process. He said, “You could be in this business for a hundred years and learn something new tomorrow. You don’t ever have it down pat and most guys that tell you they do are lying to you because they don’t. You’ve got an instrument that has 15 to 20 wooden parts and every one of those wooden parts have different densities and growth ring spacings and mineral content and weight. So those guys that sit back and say, ‘Oh, you want one with this sound or that sound and I can get you one.’ No, they can’t guarantee that. I know I can’t. I do the best I know how to do with what I’ve got, but it’s a little hard to guarantee a sound. But, I think we’re all trying to get that good bluegrass sound that Monroe’s mandolin had and that’s what everybody wants; that good woody sound.”

And it’s that final sound that, because of the very nature of being a builder, Ratliff seldom gets to see or appreciate in the mandolins he builds. This is because none of his instruments are actually broken in when they leave his shop. Ratliff said, “A new one never sounds good. They have to be broken in. You really don’t know what you’re making until a year or two later. If a guy plays once every two or three weeks, it’ll never get broken in, I don’t think. But for a guy that actually plays his mandolin every day, it’s usually six or eight weeks later. I’ve gotten this phone call dozens of times, a guy will call and say—and this call is usually on a Monday or Tuesday—‘Man, I don’t have the same mandolin I had last Friday. I took it out to play this weekend and all of a sudden that mandolin just changed. It broke this weekend.’ And that’s usually about six or eight weeks after they get it. And more than once I’ve had the same guys call back about six or eight months later and they say from that day, it got gradually better and better, but they didn’t really notice a change in the last month or so. So they got it broken in to where it’s going to be. If you are a heavy player, a new instrument will break in, in a couple of months. And usually, its a pretty quick thing, when it goes, it will go real fast.”

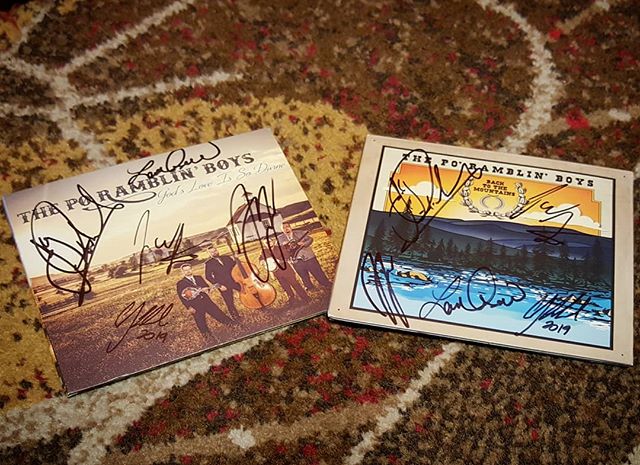

Ratliff makes traditional models of mandolins; the R-5 and R-4 are his equivalents to the Gibson F5 and F4, and the RA-5 and RA-4 are his A-style mandolins. He also makes F-style mandolas and F-style mandocellos and octave mandolins. Like most builders nowadays, Ratliff now offers two economy models that he calls his Country Boy mandolins, both in F-style and A-style. The big difference is the lack of binding and only one choice for the finish; they are made with a dark tobacco/chocolate burst in a matte finish, but those differences are only surface ones. Ratliff said, “I never make a decision until it comes time to put the color and the binding on, whether that mandolin is going to be a Country Boy or not. So all of the interior construction, quality, and materials are all the same. I don’t make a decision until fairly late in the construction process as far as what’s coming up next on the delivery schedule. So they really are a high quality instrument at a lower price. The Country Boys really keep me hopping.”

photo by Charles Johnson, mandolin world headquarters

One thing that has separated Ratliff from other builders is that from the beginning he has cultivated relationships with music stores so that they can sell his mandolins. About half of his mandolins are still custom orders for individual customers, but Ratliff keeps a steady inventory moving out of his shop and into music stores around the country, and the internet has really helped his sales. He said, “It was more of a business decision so somebody else could do the selling. Then once the internet came along, it’s nothing for somebody in Oregon to buy from a music store in Florida. So everything has seemed to work very well. I kept the best of the stores that I felt were customer oriented and had the same kind of business mind that I have, the same overall goal to give good customer service and stay in business forever, rather than make a quick dollar. The people that I have listed on my website as dealers are all good people that I trust. They are the cream of the crop in music stores.”

Something else that Ratliff does that few other builders bother with is to make videos for each new mandolin as it is finished, just before heading off to a music store. These have turned out to be a major sales tool for him. Ratliff said, “That’s one of the better decisions I’ve ever made. Once an instrument is going to a music store, my normal procedure is to play a tune on it, and tell a little bit about it, and where it’s going to, and how to get a hold of them. It’s been a marvelous tool; so much so that I can’t believe that everybody doesn’t do it. I’ve had music stores say that this guy came in and bought this mandolin and put money down on it and it ain’t even there yet.”

photo by charles johnson, mandolin world headquarters

Another aspect of his continuing success as a builder is his unusually low prices. Currently, his fully bound and inlaid R-5 sells for $3750 and the Country Boy version is under $2000. By any standard, this is a bargain, but Ratliff really believes in what he is building. He said, “I honestly and truly believe that these mandolins that I’m making now are every bit the equal to mandolins that are bringing three times as much on the market.”

The two year wait for one of his mandolins certainly supports this, but in talking to Audey Ratliff, you get the idea that his mandolins are more than just tools. They’re more important to him than that and they have shaped his life as much as he has shaped them and brought them to life. Ratliff said, “I get attached to a instrument like they’re my best friend. They’ll see you through good times, bad times, divorces, heartaches, and house fires. Your instruments are just there; they’re part of you.”