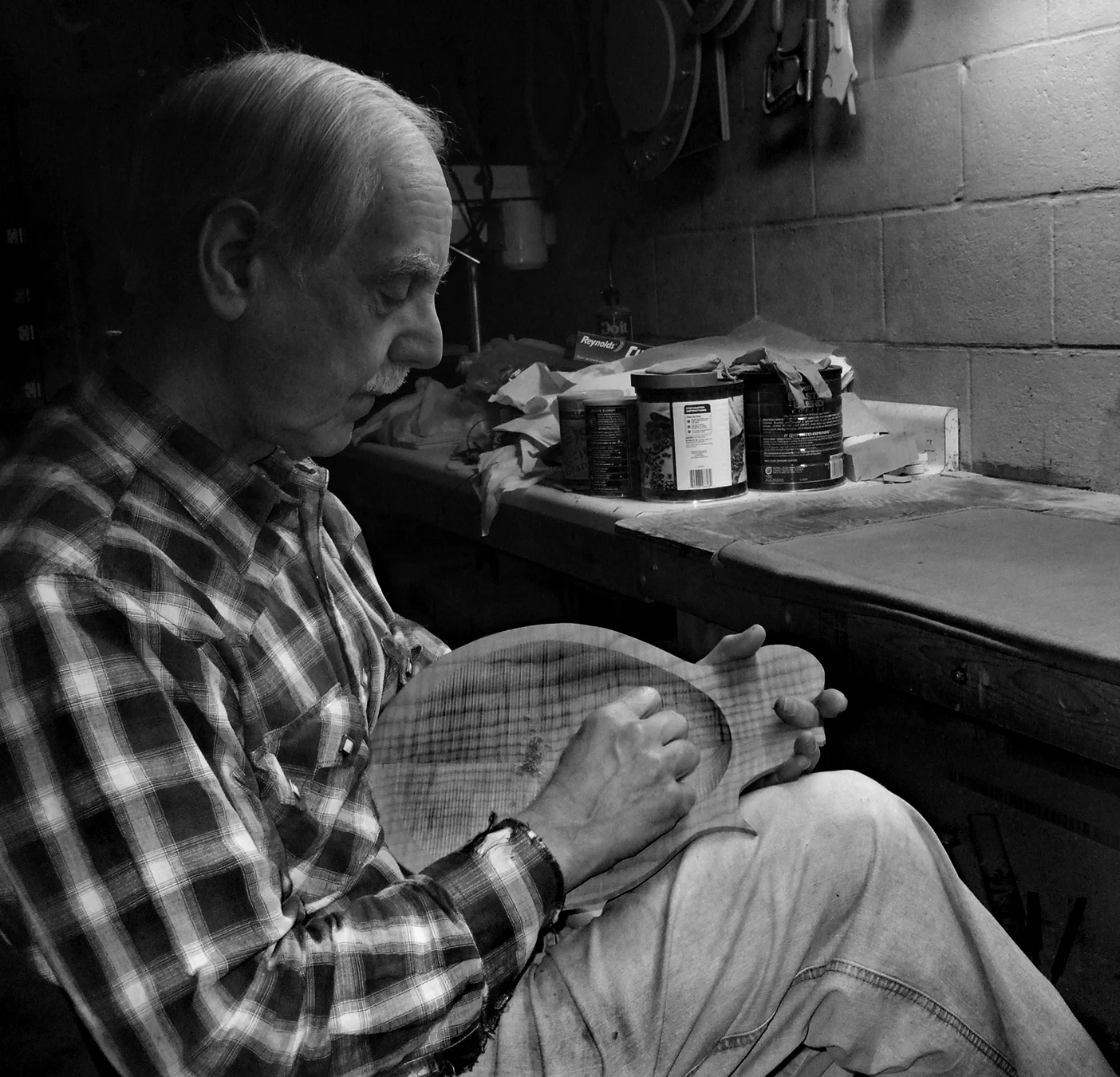

Louis Stiver:

A Life in Mandolins

by Hermon Joyner

At 78 years old, Louis Stiver has been building mandolins in Polk, Pennsylvania, for a long time. He started hand-building mandolins in 1970 and that has been his career since he went full-time in 1978. And he’s up front about the unique realities of making instruments by hand. Stiver said, “Even if you take consecutive cuts from the same piece of wood and make two mandolins exactly the same, with exactly the same shape, and graduate them exactly the same, they will sound different. And nobody has ever come up with a formula to defeat that. No two mandolins can sound the same; sound similar maybe, but not the same.”

When Stiver says this, you don’t hear frustration; if anything, you hear eagerness and even wonder, as if he can’t wait to see what each new mandolin will bring. Stiver has been able to sustain this level of excitement and passion his whole working life and it keeps him building.

When Stiver was growing up, he had that mechanically-oriented type of mind that sometimes leads a person to become an engineer or inventor. He was the kind of curious kid who liked to take everything apart to see how it was made and how it functioned, sometimes to the consternation of his parents. Stiver said, “Everything I had, I had to tear it apart to see how it worked, including my pocket watch. I tore it all apart and had the pieces scattered all over the table, put it all back together and had it run as good as it ever did before. My parents were always reprimanding me for tearing things apart.”

This facility with his hands and his innate understanding for how things work showed itself early on; even when it came to musical instruments. The seed for building mandolins was planted in Stiver while he was still a teenager, as well as the desire to play the instrument. Stiver explained, “The reason I started playing mandolin is that a friend of mine had a mandolin that was laying under the gutters of a garage, just laying there on the ground and the gutters were dripping water all over it and it was all twisted and out of shape and everything and I ended up taking that mandolin apart and putting a new top on it. I was only 14 or 15 years old at the time. I ended up learning how to play on that mandolin.” He adds with a laugh, “You wouldn’t know it by listening to how good I am, but I’ve been playing mandolin since 1950.”

That kind of “no fear” approach to life completely characterizes Stiver’s way of working and how he got his start. In the early 1970s, one person mandolin shops were uncommon in the United States. Though Gibson helped popularize the instrument through the first half of the 20th Century, by the 70s, they were in decline. Japanese companies like Ibanez and Kentucky filled the need for good quality mass-produced mandolins for many players. One-person shops in the 70s were just starting out, with the likes of Tom Ellis, Mike Kemnitzer (Nugget), Hans Brentrup, Randy Wood, Bob Givens, and Rolfe Gerhardt (Unicorn and Phoenix). Louis Stiver was part of this group, but because of how few builders there were, he didn’t have a lot of contact with other builders to help him along. So when Stiver decided to build mandolins, he just got busy and figured it out as he went.

Stiver said, “I just dug in and started doing it. For my first mandolin, I took a Gibson F-model mandolin that belonged to a friend of mine and laid it down on a piece of cardboard, drew a silhouette of it, smoothed out the points and the scroll, and ended up with an A-model. I made a half dozen or so A-models, before I made my first F-model.”

Using an F-style Gibson as his guide for building was a big help in learning how to build mandolins. This helped him to make the right decisions concerning the instruments’ construction and how to optimize their sound quality. Stiver said, “My A-models were built with an F-model type construction. There are a lot of A-models built today with an elevated fingerboard. But back when the F-model got its reputation for being superior to the A-model, that was when F-models had the elevated fingerboard so that the whole top could vibrate. Whereas, the A-models had the fingerboard laying right on the top, and the wood there was 3/8’s of an inch thick, so there was no way it could vibrate. Even when Gibson started making the F-hole A-model, they still used the same type of construction, so that half of the top was not vibrating. So the F-model was far superior, but when I made my A-model, I patterned it after the F-model minus the scroll and the points, so I had an elevated fingerboard. That’s the reason I say there’s no difference between an A and an F-model.”

Over the years, Stiver’s mandolins have earned a reputation for impeccable fit and finish, easy playability, strong volume, and clear tone. He sums it up like this, “I like them to be loud and I want everything to fit perfect.”

Probably the most famous person to play a Stiver is Jesse McReynolds, who perfected the cross-picking technique for mandolin. According to an online interview with bluegrass fiddler Jim Moss, McReynolds played a Stiver mandolin for more than 22 years and preferred the sustain of the Stiver, even up to the 12th and 13th frets, to most every other mandolin that he ever tried. Stiver remembers that mandolin very well. He said, “Actually, that one of his is really a great mandolin. It was Brazilian rosewood on the back and sides, first of all, and now I make them out of maple. But I like a good bottom end, and of course, Jesse McReynolds’ has a good bottom end on it, but his mandolin not only has a good bottom end, it has a really sharp, keen high end. A lot of mandolins that I play have a really good bottom end, but when you get past the G note on the A string, they just kind of die out. I prefer one that has a good even tone over the whole range.”

Little has changed for Stiver in the way that he makes mandolins, except for a recent addition to his modest basement workshop. He invested in a CNC machine that he uses to rough out the fronts and backs of his mandolins. It seems like putting in a new tool like this would save him a lot of time and speed up production, but Stiver hasn’t found this to be the case. He explained, “For the time it takes to build one mandolin, I only save one day, because that’s only one part of building it. You still have to scrape it and sand it and do the graduating and you still have to cut out the tone bars by hand and fit them. Everything is hand fit, so the fact that you get rid of the grunt work, you only save a day. But it is so convenient. I’d never want to go back to making them all by hand. It’s only been six months ago that I was making them all by hand. I would not want to do it again.”

He reflects back on what the rough carving entailed in the past. He said, “Back in the old days, you used a hammer and chisel to hog it out, and then I got my dupli-carver and that eliminated the hammer and chisel, and now with the CNC machine, that’s the easy way. I just can’t see, at my age, going back to doing it the way it was before. And contrary to what some people might think, it does not hurt the sound quality of the instrument because you are still hand-finishing it.”

While his neighbor, who is a CNC machinist, programmed most of the cad-cam designs into the CNC machine for the front and back plates, Stiver has been able to do some of the design work himself. He said, “I can do simple things, like I designed my own fingerboards. I like a compound radius on the fingerboards and you can buy compound radius fingerboards from Stewart-MacDonald, but their’s is not the radius that I want. Their’s is like a 7 ¼-inch radius at the nut to something like a 12-inch radius at the other end. What I wanted was a sharper radius than that. Right now, I’m making them with a 2 ½-inch radius at the nut and a 12-inch radius at the bridge. It makes them really comfortable to play. And I have another radius that’s 4 ½ to 12, and I designed those on the cad-cam machine and machine them out on the CNC.”

Though there are different opinions concerning flat or radius fretboards for mandolins, Stiver prefers to build all his mandolins with a compound radius fretboard and sees it only as an advantage for the player. He said, “I’ve never known anybody to complain about a radius fingerboard. It’s been my observation that if you’re used to a flat fingerboard, when you play a radius fingerboard, you don’t have any problem with it. But if you’re used to a radius fingerboard, and you play a flat one, you really notice it. It seems to be hard to play. There’s no downside to a radius that I can see.”

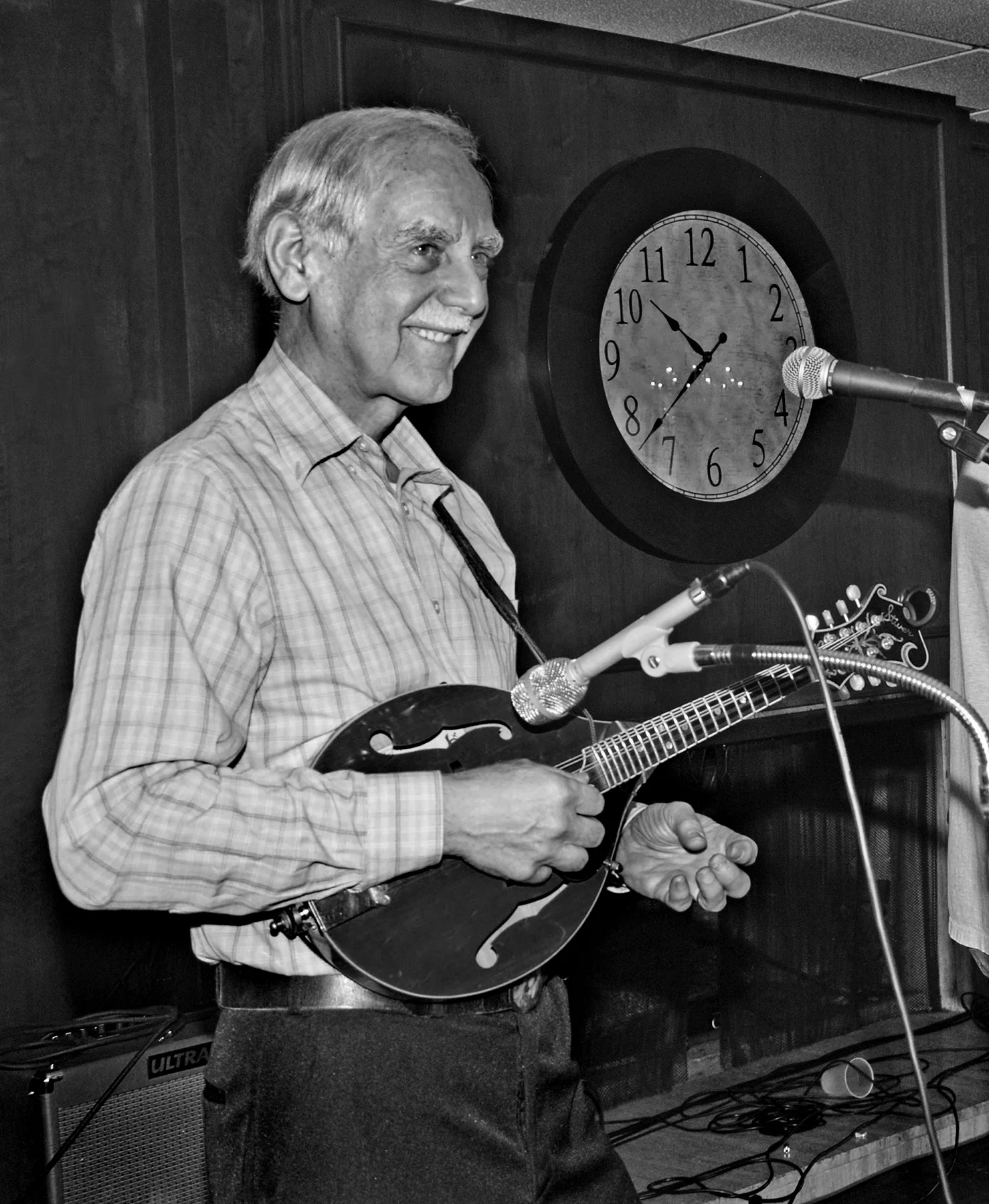

Over the 44 years that Stiver has been making mandolins and playing them—he’s been playing mandolin with The Wildwood Express bluegrass band since 1971—he’s seen several changes in popularity for the instrument. Now, mandolins are bigger than ever. Stiver said, “As near as I can tell, the way things look, mandolins are just getting more and more popular. It’s very, very seldom do I ever have somebody ask me what my mandolin is, when I’m playing. Used to, whenever we’d go out playing in my band, people would walk up to me and ask, ‘What is that?’ Almost everybody knows what a mandolin is now. People are seeing these instruments all over the place.”

Stiver has worked steadily and quietly in his chosen career of building mandolins. At one time, he used to put in 80 hour work weeks. And he’s not the kind of person to beat his own drum, but his life has had its own rewards and challenges. However, after all is said and done, he wouldn’t change a thing. For Stiver, this is the life for him.

Louis Stiver sums it all up like this, “When I started making mandolins full-time, I decided I would give it one year and if I couldn’t make a go of it in one year, I’d go back to work for somebody else. And at the time I quit to go into mandolin making, I was an automobile mechanic. After a year, I had mandolins under the beds and in the closets; everywhere you look, there were mandolins, and they weren’t selling very good. And I was going to go back to work, but my wife said, ‘Give it another year.’ Before the end of the year was out, I had all of those mandolins sold and I had orders for more. Since that time, I have never made a mandolin that wasn’t sold before I built it. Even after the economic crash in 2008, I still have never got to the point where I had built a mandolin that I didn’t know where it was going to sell. I haven’t made very much money, you make more money working on a day job, but it’s sure nice being able to work for yourself. Cause I can get up in the morning at 8 o’clock, instead of 5 o’clock, and sometimes I’m still working at 10 o’clock at night. All I have to do is walk down the stairs and go to work. And if I decide I want to do something different, I can take the day off. I haven’t worn a watch since 1978. And most of the time, I have no need for one.”

[The article was originally published in the Mandolin Magazine, Summer 2014 issue.]